Your campaign should be The Hobbit, not Lord of the Rings

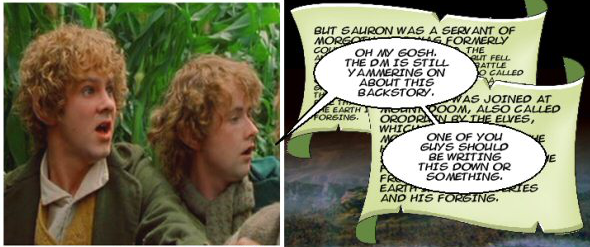

Seamus Young of the Twenty Sided blog said it first: Lord of the Rings would make a terrible D&D campaign. But let’s talk about The Hobbit.

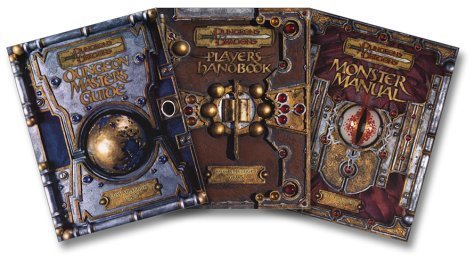

I first began playing D&D because of two webcomics: Seamus Young’s iconic DM of the Rings and Rich Burlew’s Order of the Stick. I have yet to read a webcomic that surpasses either. The former, a comedy about an epic saga gone wrong. The latter, a comedy that became an epic saga. Their influence overcame every obstacle in my way: the game’s time demands, its lingering social stigma, and even the then-high cost of entry meant little to me. My friends had the books, I had the desire, and we went boldly onwards towards adventure.

Right out of the gates, I had a basic idea of when D&D is fun and when it’s not. Were Order of the Stick a record of a real game, and Rich Burlew its DM, not its author, it would still be a wild success. Why? Because his campaign has a flexible tone. Games of Dungeons and Dragons have room for both comedic and dramatic extremes, and both can be precipitated by the players and the DM. The drama can be heightened by a tense scenario laid out by the DM, or by players sticking to their characters’ ideals and (especially) their dramatic flaws. Comedy happens easily. Everyone got together with their friends to have a good time, and people are always cracking jokes, making fun of NPCs’ names (to the DM’s chagrin), and remembering old in-jokes between players.

Lord of the Rings, in many ways, would make a wonderful D&D campaign. Tolkien’s influence on the genre is undoubtedly more pervasive than his contemporaries, like Edgar Rice Burroughs or Charles Williams. It’s an epic story, a battle between a small group of heroes and a legendary evil. There are fantastic peoples, dangerous dungeons, and incredible monsters. And yet, something is clearly missing. While Lord of the Rings is one of the greatest fantasy trilogies ever written, it doesn’t quite translate to an interactive medium.

But what about The Hobbit? Unlike its burlier cousin, the first book set in Middle Earth is a cheery children’s story, not a Beowulfish epic. And that’s what makes it so perfect a template for D&D adventures. In my experience, The Hobbit is fun to read. Lord of the Rings is challenging to read. Enjoyable, yes. Inspiring, clearly. But not fun. It is an effort to read those books. And once you’ve reached the point in your D&D campaign that it becomes an effort to play each week, you need to reevaluate your game.

With that in mind, what elements of The Hobbit have improved my game?

My stories are simpler. As a first time DM, I tried to make the most intriguing, surprising, and in-depth story I could imagine. Plot twists oozed from every crack, and the history of the world dated back thousands of years. It was a disaster. Players should never be forced to care about your story. The DM’s story binds the disparate players together, but it shouldn’t be the game’s main focus. A DM who isn’t interested in the stories their players have to tell should go write a book.

D&D gathers five or six friends around a table to tell a story together. The simplicity of The Hobbit’s plot, saving dwarven gold from a greedy dragon, is a D&D game’s greatest strength. When a DM plans out only a simple framework like this at the beginning of their game, anything can happen. Once the DM becomes the sole storyteller, and the players are just gliding along from encounter to encounter, they may as well be playing Skyrim.

I’ve stopped with all the stilted language. I may give my characters a distinctive vocal tic or style (dwarves say “aye” a lot, goblins and kobolds speak broken English), but they all talk like normal people. When all lines are improvised and must be immediately understood by your fellow players, speaking in a faux-archaic style doesn’t work. It can even draw people out of the game more than it immerses them, since suddenly they have to decode everything you say.

The Hobbit is written in common, if somewhat dated, language, and it is all the better for it. Lord of the Rings is long-winded and lousy with details.

It may be a more advanced, meatier read, but unless Shakespeare himself is a part of your gaming group (please invite me to join that table, by the way), that level of eloquence and poetry cannot be achieved at the gaming table.

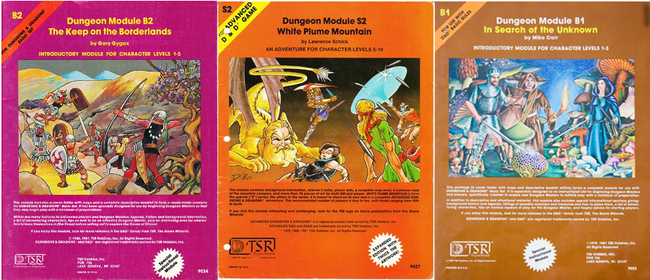

I’ve made my games more episodic. In the early days of D&D, episodic games were par for the course. TSR published many adventure modules, like Keep on the Borderlands, White Plume Mountain, and In Search of the Unknown that were designed to be like a single episode on a serial television show. Each adventure was self-contained, and could be played in any order you wanted.

The Hobbit pitted Bilbo against unique obstacles that still flowed easily from one to the next. The firefight with the goblins led directly into an encounter with the skin-changer Bjorn, and the encounter with Mirkwood elves led the dwarves into a trap set by three monstrous spiders. Every episode in the book brought Bilbo and company closer to the Lonely Mountain, but not every danger related to Smaug the dragon. In fact, Smaug’s influence was not felt until they reached Lake-Town; when they were practically at the dragon’s doorstep.

The advantage of an episodic game is that at the end of each session, the players feel that they’ve accomplished two things. They’ve succeeded at a minor objective (survived a spider attack, or found an elvish blade within a troll-hold), and they’re now one step closer to their ultimate objective. Playing small episodes is an easy way to show steady progress. Even failure (being captured by Mirkwood elves) is a success of sorts in an episodic game, because it instantly sets up the scenario for the next episode. Every now and then, a television series will have a two-parter, why not your game?

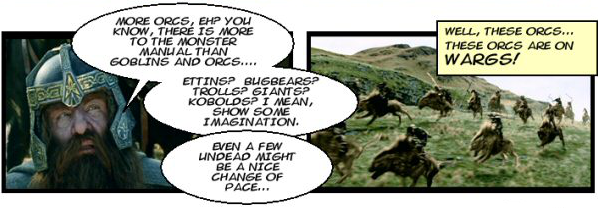

I’ve created a diverse cast of villains. This complements the episodic game very well. A Lord of the Rings style game benefits from the continuity of a single recurring enemy. Sauron’s endless orc hordes serve this need, but…

Over the course of the entire (film) trilogy, the Fellowship faces nine Ringwraiths and their flying steeds, the Watcher, a cave troll, a Balrog, orcs, Uruk-Hai (see, “bigger orcs”), goblins (see, “smaller orcs”), wolves (being ridden by orcs), and men on Oliphaunts (being helped by an army of orcs). This is done for a purpose. The point of Lord of the Rings is not to have varied monsters. Each one of these beasts is a proxy for a larger evil, one more terrible than any physical creature. But D&D is not this literary. Metaphors are powerful, but they aren’t tangible, and players need tangible foes.

Consider The Hobbit. Its rogues’ gallery holds trolls, goblins, Gollum, wolves, giant spiders, elven soldiers, Smaug the Dragon, and the countless warriors that fought in the Battle of Five Armies. Even in Lord of the Rings, the great foes, like the Balrog and the Ringwraiths, were not fair fights. They were plot devices presented by the DM to advance his story. The trolls, the spiders, and Smaug were all terrible foes, and they were defeated through player ingenuity.

At the very end of The Hobbit, Bilbo returns home, with a very tangible reward: one-fourteenth of the dragon’s hoard. An immense sum of gold, enough to live the rest of his days in comfort. He keeps Sting, his elvish blade. And he keeps the magic ring he found deep in the dungeons of the goblin hold.

The final word. Variety is the spice of life, and The Hobbit delivers it in spades. Once you have an idea for a campaign, this is how you make it thrive. Create a simple framework for you and your players to riff off of, and never get hung up on one idea. Scour the Monster Manual for new and exciting encounters, and let everything inspire you.

(Excerpts from DM of the Rings and Order of the Stick are used in accordance with Fair Use laws.)